The name Justin Fashanu is remembered in Brighton by an unusual cross-section of people: football enthusiasts, the gay community, the black community and evangelical Christians. The sheer diversity of those groups tells you a lot about the complexity of the man himself.

Born in London in 1961 to a Nigerian lawyer and Guyanese nurse, at the age of three he was placed into a children’s home with his younger brother, John, when their parents split. They were there for two years before the Jacksons, a white couple near Norwich, adopted them. Both brothers went on to a career in football, but Justin showed talent first.

To put it simply, he became a huge star. At just 20 years old he was the first black player to be transferred for £1 million. Brian Clough bought him as a goal scorer for Nottingham Forest, but things didn’t go well. Not only were the goals not forthcoming but there was a personality clash between them. Clough heard rumours of Fashanu being seen out at “that bloody poofs’ club” and suspended him. He even had the police remove Fashanu from the grounds when he arrived for training.

Signed to Brighton

A year later Fashanu was loaned to Southampton and then sold to Notts County, before signing a three-year contract with Brighton & Hove Albion in 1985.

Before he arrived, it would be fair to say Fashanu wasn’t popular with Albion supporters. While playing for Notts County the previous year, he had inadvertently hospitalised two Brighton players. However, once Fashanu had transferred to the Albion, the crowds began singing “We’ll take good care of you, Fashanu, Fashanuuuuu” to the tune of a British Airways advert of the time.

Yaasin the guitar teacher

Not long after he had arrived in Brighton, Justin bought an acoustic guitar from Southern Music in Castle Street, and staff member Yaasin Hanif agreed to give him lessons.

“I was one of maybe three black guys I was aware of in the area. I remember being so proud when I was a teenager with a player who ‘looked like me’ in the upper echelons of British football. There was something quite surreal about it all when I was giving him guitar lessons!”

Yaasin Hanif

While at Nottingham Justin had developed an interest in evangelical Christianity, something that came with him to Brighton. He became a regular part of the congregation at Emmanuel Full Gospel Church at 1 De Montfort Road.

Steve Agace remembers the first time he saw Justin play and posted this comment on the North Stand Chat forum for fans of Brighton & Hove Albion: “I remember reading in The Argus that he was a born again Christian and never swore. Fifteen minutes into his first pre-season friendly someone clattered into him and you heard the word ‘bastard’ proclaimed by Fashanu”.

The Albion were based at the Goldstone Ground opposite Hove Park. “After training he’d go for lunch with the other players in Hove Park Tavern. He was an absolute darling,” posted Philip Rees on the Brighton Past Facebook group.

Regency Square

The club gave Justin the use of the basement flat of 26 Regency Square, where he was soon visited by long-term friend and fellow footballer, Neil Slawson. “When I heard that Justin went to Brighton I was thrilled, because not only was it my hometown, but I had been on trial with Brighton the year before and I knew the squad and thought, oh he’s going to do great there.

“I went to go visit him and right out of his mouth he goes, ‘You can’t live with me here.’ I said, ‘I wasn’t asking,’ but he says, ‘Yeah, cos I’m ducking and diving all the time and it wouldn’t be a good match’. I took that to mean ‘you’re going to cramp my style’.

My personal opinion is he loved Brighton because he could be freer and there were more people of like-mind and like interests.

Neil Slawson

It just allowed him to be freer because he was truly conflicted. I don’t think he’d have been as much in conflict if he wasn’t religious and in the public eye.”

Terry the neighbour

Fairly soon fellow Regency Square resident Terry Wing struck up a friendship with Justin. “My bedroom’s right at the very top, and we’d sit at the window and just watch people go by and chat. He was a lonely soul, he said he was a born-again Christian, which he wasn’t. He gave himself that title to offset any suggestions about his sexuality.

“I’d be like his handbag – if he wanted to go out to a restaurant for a meal with a friend, it would never be booked in his name, I’d book it.”

Terry Wing

The Beacon Royal in Oriental Place was Brighton’s premier gay venue at that point. “We went down to the Beacon quite a few times. He stayed quite close to me. I was there to protect him.”

On one evening there they bumped into the infamous brothel keeper and party hostess Cynthia Payne. But back to football – Justin had arrived in Brighton with a longstanding left knee injury. During his first season a football stud nearly shattered his right knee, which promptly ended his time with the Albion. He had played just one season, made 20 appearances, and scored only two goals.

Karl the football fan

The injured Justin met Karl Heyman, an 18-year-old Brighton resident and football fan, through his church. Karl said: “It was almost like that was his escape from everything he was involved with.

“The insurance policy meant he got paid a stupid amount of money and he was trying to justify in his own mind, morally and ethically, why he should be receiving this money when he’s not doing anything. We played snooker in Castle Street and we played a bit of tennis in Preston Park, and he used to go out on the back of my motorbike.”

Karl accompanied Justin out to pubs and clubs, including The Chequers Inn on Preston Street. “We went in there a few times, it was a very gay-friendly sort of pub.

At that point he hadn’t come out, but all my friends ribbed me because they all thought he was gay.”

Karl Heyman

Karl remembers one trip to Brighton’s Palace Pier. “He bought a vanilla ice cream and covered all his mouth with it and then walked along, being black, vanilla ice cream, he just looked like a kid with ice cream all over his face. He was just doing it for laughs, and because he’s a big strapping lad and he’s a good-looking guy, he’s getting all the attention, so he was an attention seeker but for all the right reasons.”

Kevin the art student

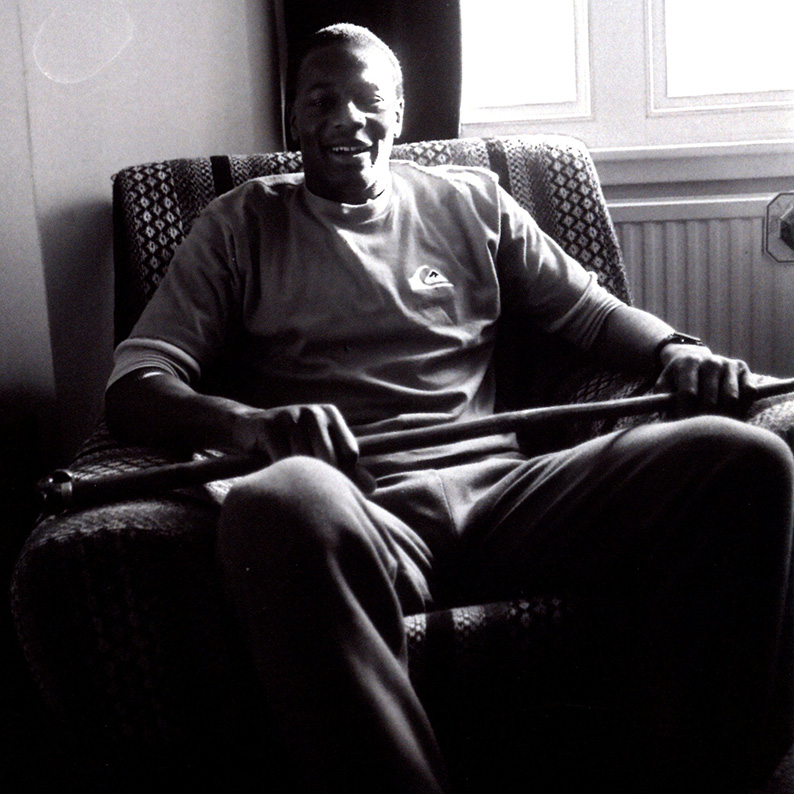

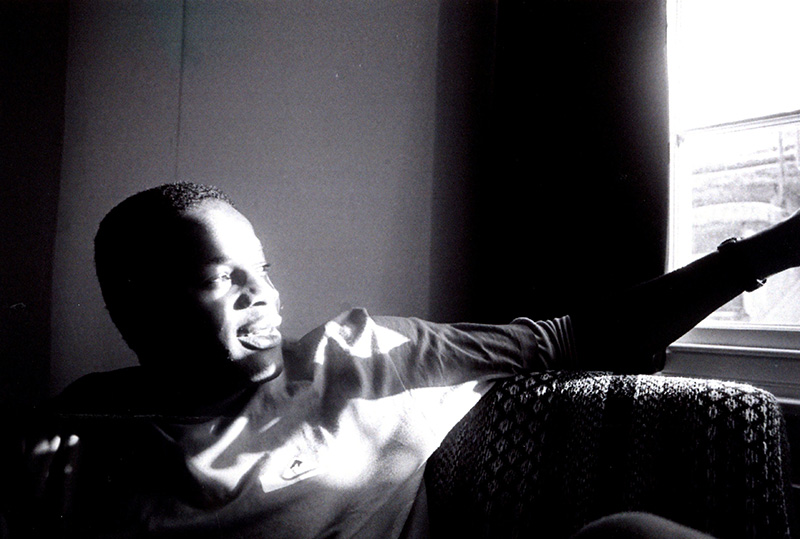

Another friend Justin made in 1986 was Expressive Arts student Kevin Weaver. “He was on crutches hobbling along the seafront near the main pier, and as a lifelong Norwich supporter I immediately recognised him and introduced myself. He invited me to his flat one Sunday and I met some of his Christian friends. He was keen to convert me, but I told him I wasn’t interested.

“I found his flat dark and quite depressing. He didn’t have much furniture and it was devoid of character, personal touches or warmth. It was basically one long floor with a galley type kitchen. However, the flat was in contrast to Justin’s character, which was open, warm and very friendly. He had a bright white smile and his eyes lit up. His laugh was infectious too and he was interested in everyone.

“We immediately hit it off, though he never mentioned his struggle with his sexuality. We went to several straight clubs including Savannah – I think we saw Princess, a black soul singer from London – and The Escape Club [now Patterns on Marine Parade]. We didn’t seem to discuss football much – he wasn’t full of himself and boastful at all. He seemed a bit lost to me.”

London to Los Angeles

Justin paid for a unsuccessful operation on his knee in London, then another in Los Angeles, which worked, and after his rehab he signed to play for LA Hearts in 1988.

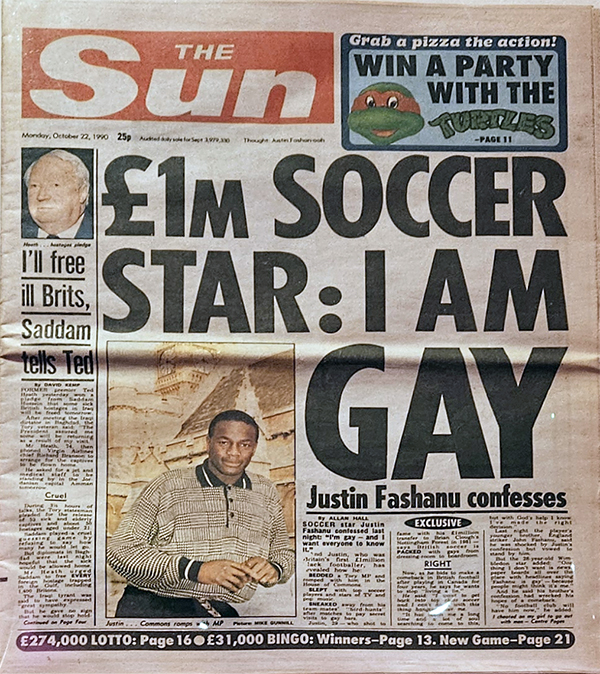

In October 1990 Neil Slawson remembers: “He actually was living with me in California and he told me ‘I’ve had an offer’ from I think it was The Sun. ‘They want to do a story on me’ and I said, ‘What’s the story?’ And he said, ‘To say that I’m gay’. At that time he was borrowing money from John to stay afloat. He said he would get like £100,000 or something and I said ‘Be very careful how you tread. How is this going to affect your future in the game?’ I remember him saying, ‘I just can’t even imagine my life without football’.”

The Sun’s headline, ‘£1m Soccer Star: I AM GAY’, and ensuing press articles had a huge impact. In brief, his brother John, and Justin’s own church, turned their backs on him. He managed to keep playing football but moved from club to club around Europe, Canada and the US.

Back in Brighton

It seems Justin returned to Brighton in 1996, as he was seen out socialising. Mark Phillips remembers: “I met him at a friend’s mixed party in Palmeira Square [Hove], in white shirt and jeans, he was with a couple of gay friends.” He recalls Justin making a comment about being gay. “He thought it would be easier to tell the world, but the world wasn’t ready.”

Iain the clubber

Iain Gowers met Justin a number of times that summer. “My friend at uni was the boyfriend of the owner of Revenge, he used to introduce me to all kinds of people in the nightclub. I do remember noticing that he was definitely athletic, quite tight jeans and a t-shirt, but nothing attention seeking. I think he just wanted to fit in. He wasn’t at the end of the dance floor dressed in glitter going ‘I’m Justin Fashanu’.

“I remember asking about his brother and he told me ‘My brother’s not spoken to me for a couple of years.’” Later that evening Iain was approached by a stranger who pretended to know Justin. It turned out to be a journalist fishing for information.

One night Iain and Justin happened to be leaving at the same time. “We both walked down the stairs and he stopped me and said, ‘You will need to wait up here for a bit’. And I’m like, ‘Why?’, especially being 20 and being told what to do. And he said, ‘You don’t wanna be outside. You’re the perfect person that they want me to be photographed with’. I said to him when I saw him next, ‘Does that mean that they follow you home?’ He said ‘Yeah’, he gets his taxi home and then they literally drive up and sit outside and wait for him.”

“I tried my best”

In March 1998, a 17-year-old American youth accused Justin of sexual assault. The age of consent was 16, but homosexual acts were illegal in Maryland at the time. Justin feared he would be presumed guilty and fled back to the UK. On 3 May he was discovered hanged in a garage in east London. Towards the end of his suicide note he wrote “I tried my best. This seems to be a really hard world.”

In a tragic twist, art student Kevin Weaver, now a photojournalist, was sent to capture the location of a celebrity suicide. “I saw a yellow and green Norwich City scarf tied to the door handle. I was stunned. It was a tragic end for a lovely, misunderstood person who I counted as a friend.”

This research was picked up by The Argus who wrote their own piece: Historian remembers former Albion striker Justin Fashanu on 15 October 2020.