You probably won’t recognise the name, but cinematographer David Watkin worked on some of the biggest films of the ‘70s and ‘80s – Catch 22, Chariots of Fire, Yentl, Out of Africa and more. Not quite in the same league it must be said, but there is also a Brighton & Hove bus named after him. And then there’s ‘Wendy’… but we’ll come to that later.

It took David a while to discover his cinematic talent. Born in Margate in 1925, his early passion for music was discouraged by his father and he enlisted in the army aged 19. He was not a natural recruit and was reprimanded at one kit inspection: “You’d lose your bollocks Private Watkin, if they weren’t in a bag.”

He left the army aged 23, too old to pursue a career in music, so he picked up a camera and joined the Railway Film Unit. It was here that he first encountered an out gay man – well, as ‘out’ as you could be when it was completely illegal. David remembers his own innocence: “‘Had I tried the cottage up on the concourse?’ I had not and spent a confused half hour looking for what I imagined would be a cosy tea-room with a simulated thatched roof.”

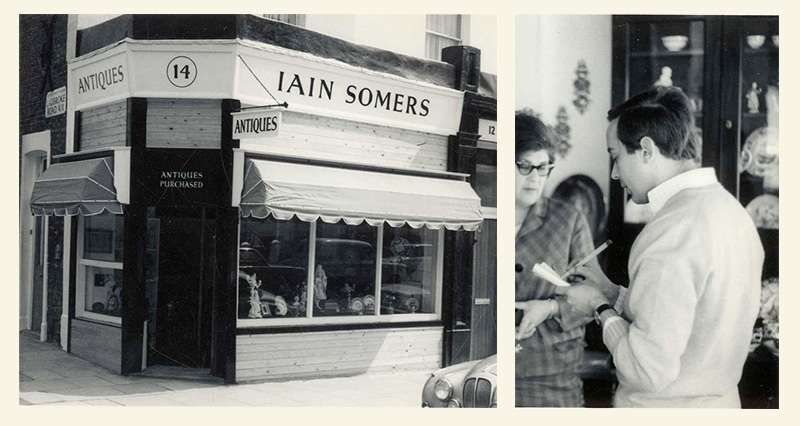

In the 1950s, David and his boyfriend Iain Somers, an antiques dealer, moved into a flat in London. David spent the next 10 years honing his film-making skills and rose to become director of photography.

After going freelance he worked on TV commercials. His talent was beginning to attract attention and in 1964 he created the intro sequence to the James Bond film Goldfinger. Before the decade was over he’d worked on The Beatles‘ film Help!, and The Charge of the Light Brigade, for which he received two BAFTA nominations.

The move to Brighton

In 1970 David and Iain moved into Sussex Mews in Brighton. As close friend artist-designer Rachael Adams describes: “They just bought number 6 at first, then they bought number 7 and then number 8, and then it all got knocked through. Iain was an antiques dealer. So most of the beautiful furniture came from there.”

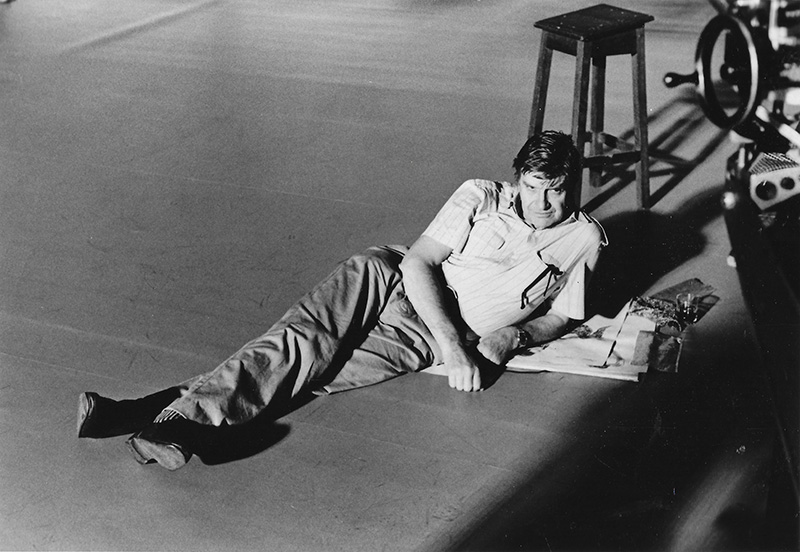

That same year, another of his films came out: Catch 22, an American black comedy of a war film. Rachael recalls David describing how the idea to light it came “from walking along Kemptown seafront. Those parts of the autumn and winter in Brighton where you can look out to sea and you can’t see a horizon, it makes you feel so isolated and weirdly claustrophobic. It struck him that that would be the perfect way to light Catch 22, these people stuck in this insane situation.”

He made two very different films with director Ken Russell the following year: The Devils starring Vanessa Redgrave and Oliver Reed, with set design by Derek Jarman; and The Boy Friend starring Twiggy in a pastiche of ‘20s/’30s musicals. Both camp classics in their own weird ways.

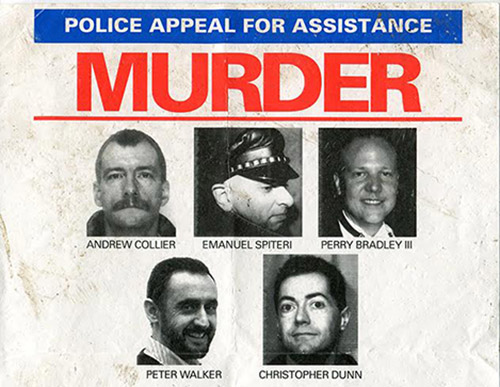

After 21 years together, Iain Somers died in 1974. Another of David’s close friends, Chris Mullen, remembers: “David told me that he was much more promiscuous than Iain and he said, ‘I want complete sexual freedom in our relationship’. Iain got more and more depressed by this, and he killed himself.” Rachael adds: “Iain was David’s big love. It was a lifelong grief for David.”

Diamond

Graham Ingram ran a car business from the Mews in the ‘70s, later becoming the landlord of the Somerset Arms (58 St George’s Road) and says “David was a diamond.

“A lot of stars used to go and frequent his house, especially if there was a film in the offing. I know one of the guys that done Robin Hood [Robin and Marion, 1976]. This Robin Hood character [Sean Connery] was climbing a tree and David Watkin being David Watkin went and looked up his kilt. That made me really chuckle.”

But seriously, “his skill as a cinematographer was actually… it was unique,” says Chris. “He made films that look like nobody else’s. The sight of the American airport (Catch 22), being bombed by its own planes is absolutely sensational, because it’s not conventional film lighting, it’s the actual light of the bombs.”

David was not interested in receiving awards but had ten years of them, starting in 1981 with Chariots of Fire. The crisp filming of the athletes running in slow-motion across a beach was a novel effect created by him.

In 1983 David finished the Barbra Streisand film Yentl. “Barbra Streisand was often on the phone because she loved David for several reasons, all of them to do with the fact that he could make her look wonderful and reduce the size of her nose,” says Chris.

David completed Out of Africa in 1985, for which he won five awards, including an Oscar and a BAFTA. Many guests in Brighton would remark on that Oscar, and the fact that it was holding open the door of his downstairs toilet. “He didn’t value fame in any way, he valued kindness,” remembers Rachael.

Wendy

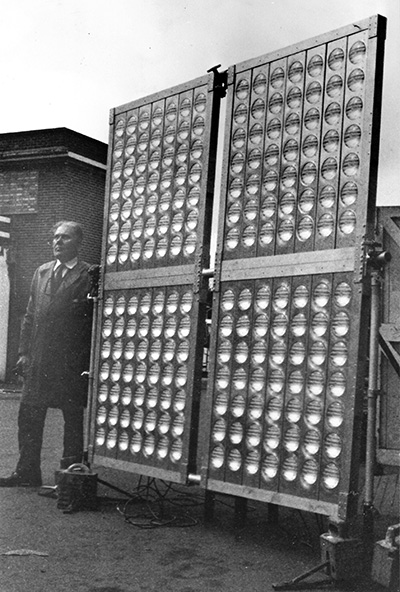

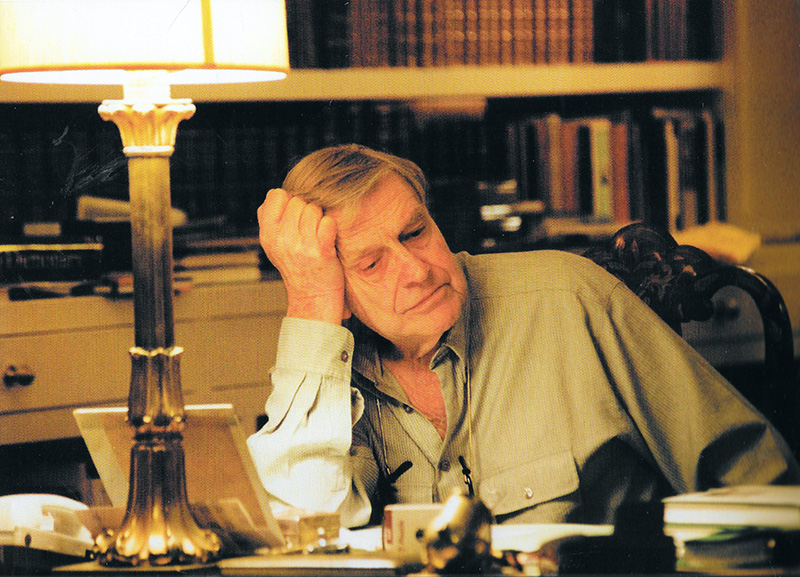

The painterly quality of the light in the film was created using his own invention: The Wendy Light (pictured).

In simple terms (that I can understand), it is a large bank of lights raised high on a cherry-picker. He called it Wendy after the camp name that was given to him by a group of electricians in his early days. The light is still used by film crews today.

Chris remembers one occasion in Brighton: “I was with him by the cheese shop and a man outside the shop said ‘Wendy!’ and he turned around and said ‘Yes.’ This man said ‘No, I was looking for my wife’. And Watkin said, ‘I’m sorry, I thought you were an electrician!’”

Chris taught Narrative Illustration at Brighton Polytechnic / University from 1989, and David gave regular talks to his students. One such student was the aforementioned Rachael, who went on to design Watkin’s autobiographies: Why Is There Only One Word for Thesaurus? and Was Clara Schumann a Fag Hag?.

She recalls: “I felt very quickly that we were fulfilling some kind of role above and beyond potentially designing a book. Something about his childhood meant that he was always looking for family.” Chris continues: “It was the family he always wanted because his family professionally was the film crew that he worked with.

“At the end of every gig he would jump in a taxi at Brighton Station and get this feeling

of burning off all the frustrations of his professional life. He could put his music on at 4am, and, because all the rooms around him were let out on a peppercorn rent to his friends, nobody would object.”

Making friends

Duncan Lustig-Prean became friends with David Watkin in 1997 after David wrote to congratulate him on his campaign to stop the UK government from dismissing military personnel on the grounds of their sexuality.

“He invited me to dinner in Sussex Mews. His place was really old-fashioned. He had a harpsichord piano, which he played superbly. Which of course is what he really wanted to be, a musician.”

David much preferred to entertain at home rather than visit pubs and clubs and liked to show guests video outtakes. He had footage of the Queen Mother attending an event, her steward wearing full Highland costume. As the steward excused himself with a profound bow the image transitioned from the Queen Mother’s face to his arse.

Duncan continues: “David was no angel. He would have call boys come down from London.” David was open about this himself: “My life would be vastly impoverished had I never encountered a rent boy.” He met them through the Olympus Lads agency in London and went on to help a number to get out of that lifestyle.

As Rachael recalls: “He had huge empathy for these boys, he would develop these crushes but he was so kind and he wanted to help them and improve their lives.”

Lifetime achievements

In 2004 David was awarded two lifetime achievement awards, and when asked for an inspirational quote by one of them he replied: “One tries not to fuck up.”

Two years later he entered into a civil partnership with ex-Olympus Lad turned embalmer, Nicky Hands, at Hove Town Hall.

Duncan Lustig-Prean said of David, “I got the impression that being in a relationship was not his natural state of being. So, when his last relationship came along it was a surprise. But I think that for his final months, it made David happy.”

David passed away in February 2008, just 12 months after being diagnosed with prostate cancer. As for his belongings and archive, Chris remembers Nicky saying: “Oh, I’m gonna throw them all away. I don’t want the house to be a museum”. Sadly that is pretty much what happened.

Nevertheless, David’s cheeky sense of humour remained with him until the end. The glossary of lighting terms at the back of Clara Schumann includes these definitions: ‘Cottage: meeting place with toilet facilities’ and ‘Honey wagon: mobile toilet for film crews’.

I’m going to leave the last word on David to his friend Barry: “He was a proud gay man of his generation. His career could have taken him anywhere in the world, but he chose to live in his beloved Brighton.”

If you want to find out more, the David Watkin Archive is still online.

All David Watkin quotes come from his autobiography Was Clara Schumann a Fag Hag?.